Immunotherapy for Breast Cancer: A conversation with Dr. Daniel Silver

2020-10-13

In honor of breast cancer awareness month, UCIR spoke with Daniel Silver, MD, PhD of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. Dr. Silver is a medical oncologist who specializes in the treatment of patients with breast cancer. He is the director of basic science and research in medical oncology at Thomas Jefferson, and wrote his PhD research on basic immunology.

UCIR: How have advances in immunotherapy impacted the care of patients with breast cancer?

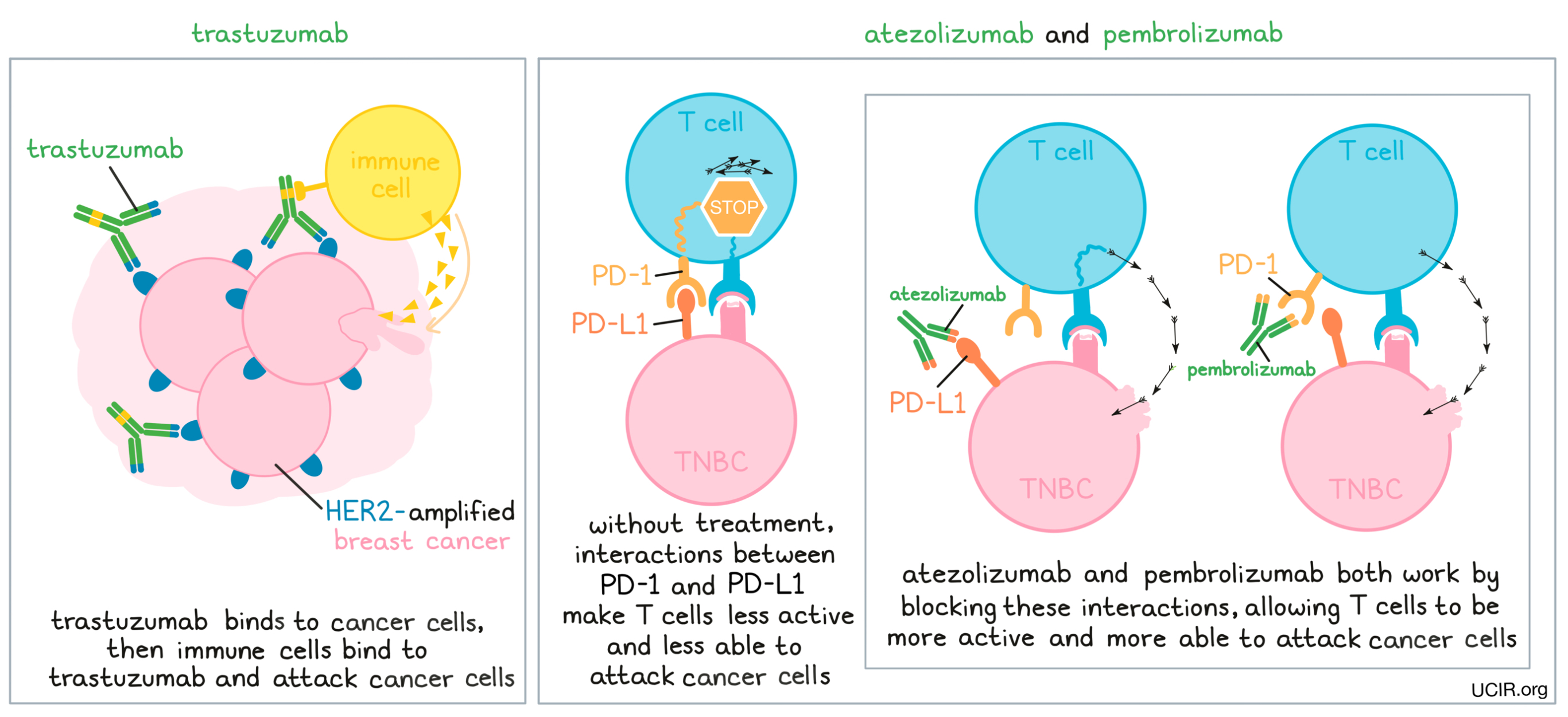

Dr. Silver: HER2-amplified breast cancer, in a certain sense, has been the earliest target of immunotherapy. HER2 is a receptor that drives the growth of HER2-amplified breast cancer, and the very first antibody to be used in cancer therapy, trastuzumab – known by the trade name Herceptin – targets that receptor. This antibody has been in use for a very long time now, but when it was first shown to be useful, it wasn’t entirely clear whether it worked by inhibiting the function of the HER2 growth factor receptor, or whether it attracted an immune response. Through a variety of clinical observations and further clinical development, it has since become clear that this antibody does attract an immune response against HER2-amplified breast cancer as probably the main way that this drug works. There has also been further development of HER2-directed therapies that involve modifying antibodies to attract an immune response better.

More recently, for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), there are now two FDA-approved treatments, pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and atezolizumab (Tecentriq), in the first-line setting (before any other treatments are given for metastatic disease), and these treatments have been completely practice-altering. For metastatic TNBC, first-line therapy now involves inhibition of the PD-1 pathway in addition to chemotherapy. This has been shown to decrease the rate of progression of disease, and occasionally there are some very long-term responders. Metastatic TNBC is a very lethal type of breast cancer, and so we are very gratified to be able to offer patients the chance of a long-term response, but unfortunately it is not as common as we would have hoped. In some other types of cancer, there might be 20% or 30% of patients who have very long-term responses to immunotherapy, who wouldn’t have otherwise had long-term responses. In breast cancer, these long-term responses seem to be much rarer – more like on the level of about 5% or so. Of course, when they do occur, they are nothing short of miraculous. And even if patients don’t have a long-term response, on average, their length of response is better than with chemotherapy alone, so incorporating immunotherapy has completely changed our practice and practice throughout the world.

UCIR: What makes a patient a good candidate for immunotherapy?

Dr. Silver: First of all, for a patient to qualify for immunotherapy, they must meet the criteria for the FDA-approved drug that they would be receiving. Right now, both of the FDA-approved drugs for TNBC require that a molecule called PD-L1 be measured on tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating white blood cells. We also now know that the higher the infiltration of the tumor with lymphocytes, the more likely a patient is going to respond to a variety of therapies. Still, our understanding of the rules of who is going to respond to immunotherapy and who is not is far from complete, and it is currently the subject of a huge amount of research. So it’s complicated and it’s evolving, but understanding better ways to select patients is part of a commitment of the field to move towards immunotherapy. We also have a long way to go to understand what the best other therapies are to use in combination with immunotherapy to increase the number of patients who respond. That’s a huge mystery, and a lot of work is going to be required to figure out what the best combinations will be.

UCIR: What are some of the hurdles to treating breast cancer with immunotherapy?

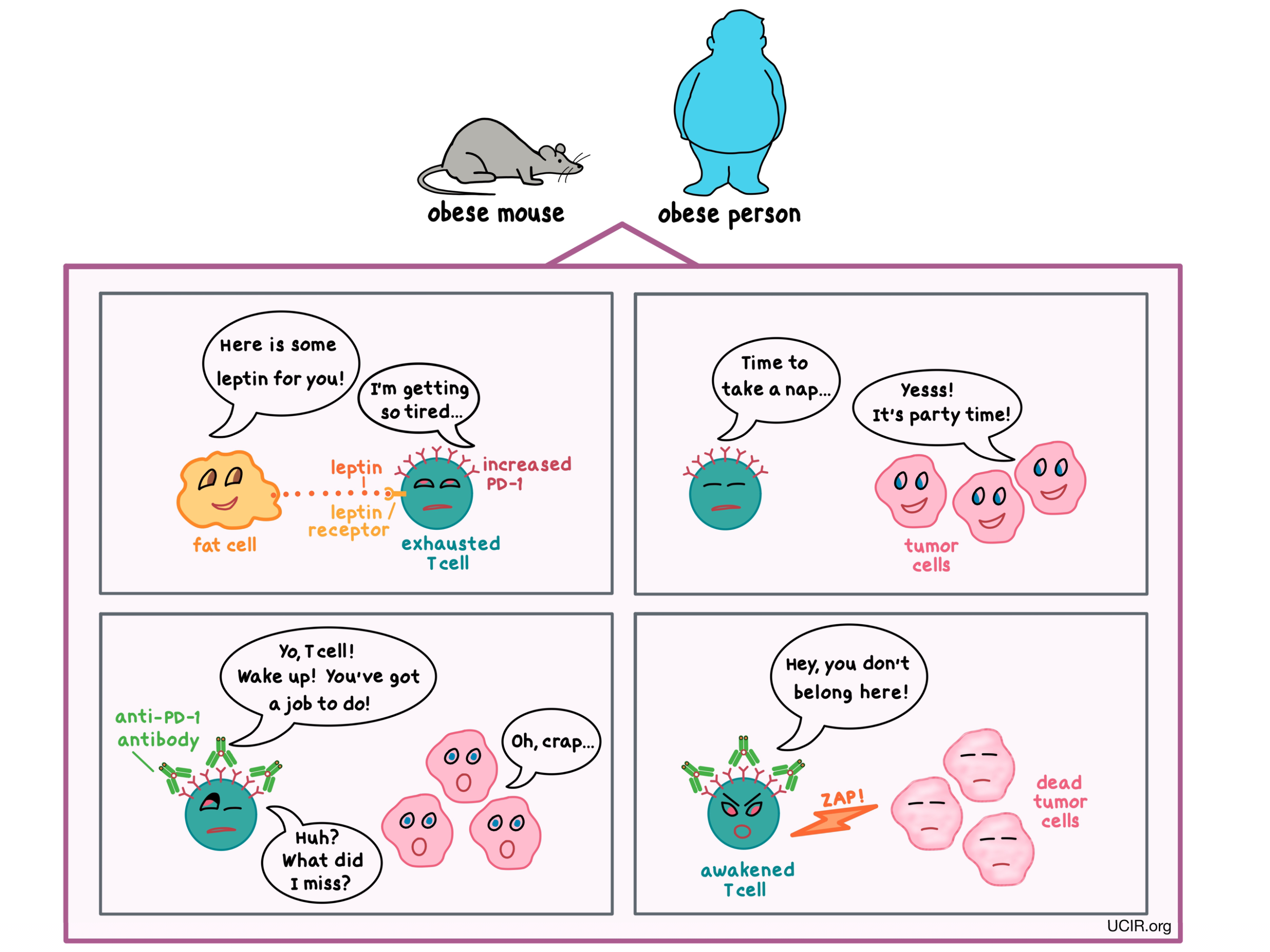

Dr. Silver: Medical oncologists have all grown up hearing stories about very rare cases of widely metastatic cancer where the tumor miraculously clears without any treatment. In retrospect, we think that these were cases in which robust tumor immunity spontaneously emerged. Supporting this, the types of cancers that have seen these rare reports of random tumor clearing, mostly melanoma and renal cell carcinoma, have turned out to be the cancers that have benefited the most from immunotherapy. In breast cancer, those reports are essentially non-existent, which is an indication that it is going to be a somewhat harder target.

In general, tumors with many new antigens compared to normal cells are more likely to respond to immunotherapy, and a very rough measure of new antigens is the frequency of mutations in the DNA of the cancer. In that regard, breast cancer is not particularly high on the hit parade compared to cancers like melanoma, MMR-defective cancers, or smoking-related cancers, but there are occasional breast cancers that have fairly high mutational burdens. In general, triple-negative breast cancer has the highest rate of mutations, and that is partly why it has been the subject of such intense clinical development for the application of immunotherapy.

Another issue is that breast cancer isn’t one disease; it’s really at least four different diseases with the same location of origin, but probably different cells of origin, and certainly different molecular and clinical characteristics. For certain patients with HER2-amplified breast cancer or TNBC there are immunotherapy options available, but for patients with estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer, which makes up about 70% of all breast cancers, there are not. A recent and very innovative clinical trial called I-SPY 2, however, has provided initial evidence that by adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy in newly diagnosed non-metastatic patients, there may be an advantage.

UCIR: In what ways could immunotherapy improve the quality of life for patients?

Dr. Silver: In general, the side effects of immunotherapy are, at least on a day-to-day basis, more tolerable than the side effects of chemotherapy. I do think it’s important when we’re talking about quality of life not to neglect the fact that unleashing the immune response in some unfettered way sometimes causes side effects of its own. We understand now clinically that there are a number of autoimmune phenomena that these drugs can unleash. Most of these are manageable – some are minor, some are not-so-minor, and on rare occasions, some are catastrophic. It’s important to keep in mind that oncology is still a high-stakes game, and it really requires clinical expertise to judge the risks and benefits of various therapies. In breast cancer, there isn’t a whole lot of activity with monotherapy of immunotherapy, at least with the tools we have now, so we haven't been able to move away completely from the chemotherapy backbone, and we are currently combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy. Immunotherapy may allow us to back away to some degree from the intensity of standard chemotherapy so that the day-to-day quality of life is a bit better, but with the addition of immunotherapy, the duration of response is clearly improved, so on the grand scale of things, there is no doubt a benefit in terms of both the quality of life and the duration as well. Of course, the best way to improve the life of somebody with metastatic breast cancer is to prevent it from happening in the first place.

UCIR: How could immunotherapy be used to prevent the spread of breast cancer?

Dr. Silver: Most of us hope that adding immunotherapy to the initial therapy of high-risk localized disease may decrease the risk of eventual spread. This is a very active area of current clinical investigation. Right now, the FDA approvals for immunotherapy drugs only cover patients whose disease has spread outside of the confines of the breast and outside the nearby lymph nodes in the armpit, so treatment is currently limited to patients with widespread disease.

There is now a huge amount of work to move immunotherapy into the treatment of early-stage breast cancers and potentially decrease the probability of systemic relapse. I am very optimistic that immunotherapy in the early treatment of breast cancer, before it has spread, will offer a way to decrease the chances that a patient’s breast cancer will come back. That, in addition to everything else, would be a very significant clinical advance.

UCIR: Do you see immunotherapy as a promising approach to treating breast cancer in the future?

Dr. Silver: Yes. I’m very enthusiastic about immunotherapy. I was trained in an era where immunotherapy was a very obscure part of oncology, and it wasn't at all clear that the efforts of the few pioneers who were courageous enough to go into cancer immunotherapy were going to pay off. I was very lucky to have a patient who had metastatic triple-negative breast cancer who was put on one of the earliest monotherapy trials of a PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor in the second-line metastatic setting. This was a patient, who on average, we would have expected to have a life expectancy of a year to a year and a half, and now five years later, she is alive and, as far as we can tell, disease-free. That kind of experience takes your breath away, because medical oncologists who treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer know that never happens with conventional therapy and that this is not a coincidence. The last decade or so of research and clinical trials has made it abundantly clear that immunotherapy is here to stay and I am completely sure that it is here to stay in breast cancer.

by Lauren Hitchings

References:

n/a