Antibiotics do not play nice with cancer immunotherapy

2019-12-20

Why does immunotherapy work for some cancer patients but not others? A number of immunotherapy drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors have been approved in recent years for the treatment of certain types of cancers, but many patients do not benefit from such treatments, and scientists have been working hard to figure out why this is the case. In a recently published study, researchers found that the use of antibiotics is one of the factors that could worsen response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

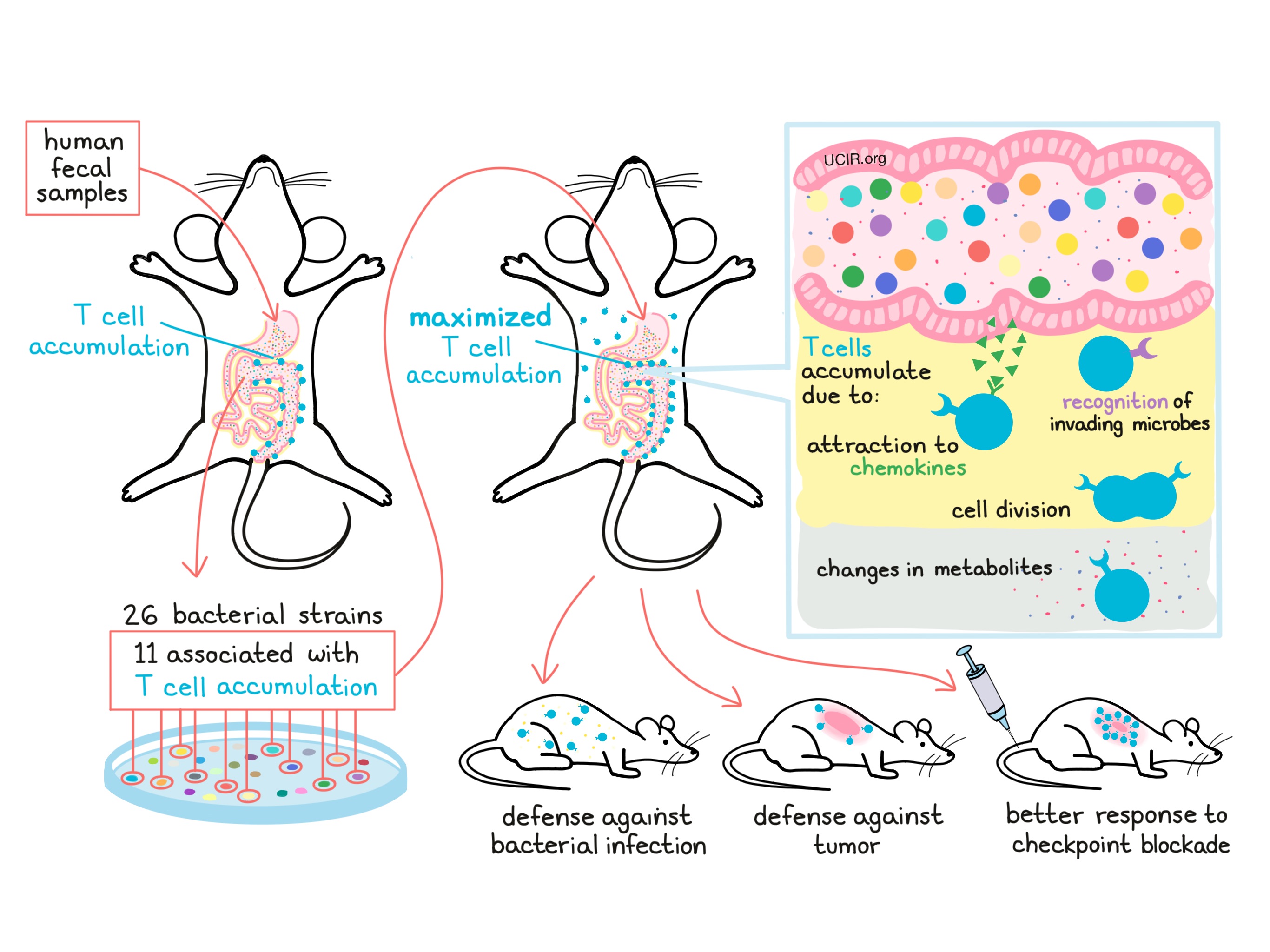

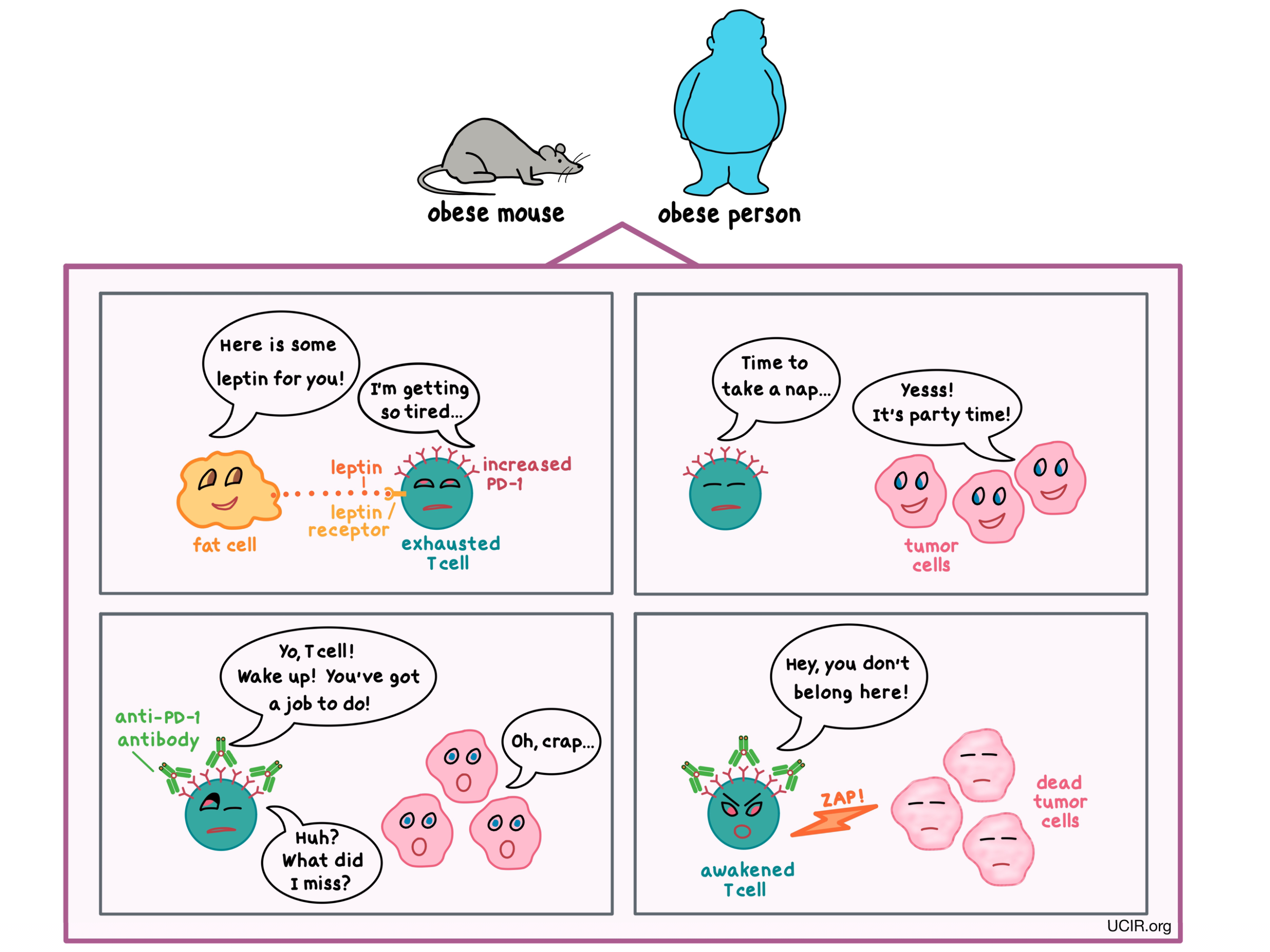

Immune checkpoints (such as PD-1 and CTLA-4) are molecules found on the surface of T cells – the major players in preventing cancer growth. These immune checkpoints have a normal and necessary function to keep the immune cells from getting out of control and attacking healthy cells. Tumors can co-opt this safety mechanism and use it to avoid destruction by the immune system by rendering T cells dysfunctional. Immune checkpoint inhibitors – therapeutics which block the action of the immune checkpoints – can restore function to the T cells and enable them to kill tumor cells. This positive response happens for some, but not all treated patients, and investigators are steadfastly searching for clues to indicate why checkpoint inhibitors are not more universally effective. Surprisingly, over the past few years, research has shown that the gut microbiome – the population of microbes in the gut – affects response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Since antibiotics can alter the gut microbiome, the use of antibiotics became a suspect in immunotherapy resistance.

A group of researchers, led by Arielle Elkrief, Philip Wong, and Bertrand Routy, took a look at 74 patients with advanced melanoma, 10 of whom received antibiotics within a month prior to initiating immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy that targeted either PD-1 or CTLA-4. The researchers found that none of the patients who received antibiotics responded to treatment, while one-third of the patients who did not receive antibiotics did respond to treatment – either with a decrease or a complete disappearance of the tumors. In addition, patients who received antibiotics had their disease worsen sooner than patients who did not receive antibiotics.

The results of this study reinforce the idea that antibiotics can lower the diversity of the gut microbiome, potentially reducing levels of bacteria that help enable response to immunotherapy. However, it remains unclear whether antibiotic use causes resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or if it is only associated with such resistance. It is also important to note that other factors not analyzed in this study may influence the diversity of the gut microbiome, and these include diet, country of origin, some medical conditions, and other medications. While antibiotics may be necessary to treat certain conditions, the authors of this study recommend their judicious use in patients with advanced melanoma.

by Anna Scherer