The surprising effect of obesity on the response to cancer immunotherapy

2018-12-05

Obesity is a known risk factor for the development of certain types of cancer. However, how it affects the immune system as the tumor develops and progresses and how it may influence a patient’s response to immunotherapy is not well understood. In a recently published study, a team of researchers led by William Murphy and Arta Monjazeb at the University of California Davis School of Medicine encountered seemingly paradoxical results – heavily overweight patients had a weakened immune system, but at the same time showed a better response to a certain type of immunotherapy called checkpoint blockade.

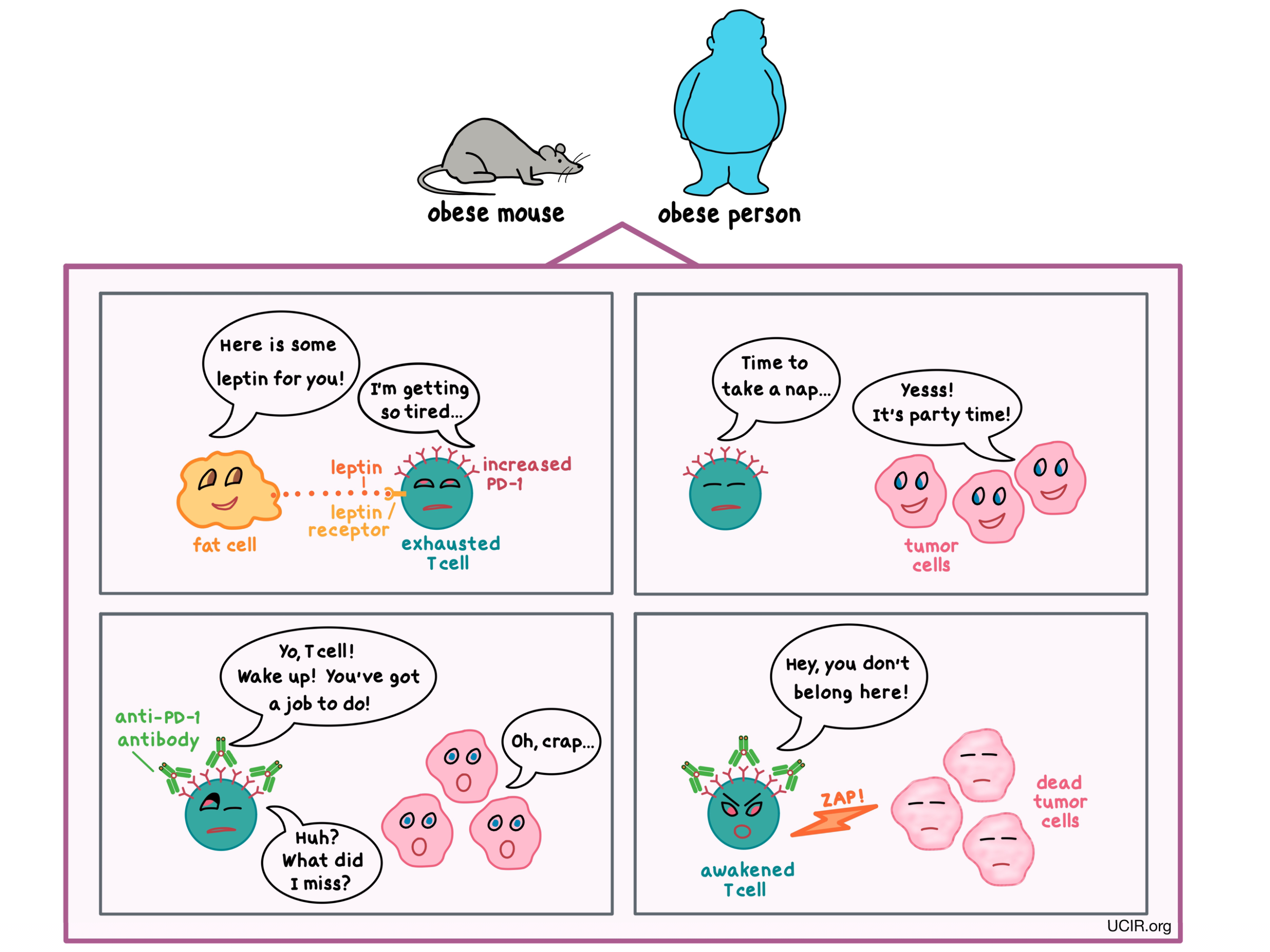

The research team began by studying T cells – the immune cells that play the main role in keeping cancer in check – in lean and obese mice. Obese mice had more dysfunctional and exhausted T cells compared with lean animals. Similar effects were seen in monkeys and in humans. When cancer was added to the equation, the researchers saw that in mice with melanoma, obesity sped up both the growth of tumors and the exhaustion of T cells.

How was obesity subverting the immune system’s ability to keep tumor growth at bay? The scientists already knew that in obesity, leptin – a hormone released by fat cells that helps to regulate appetite – is elevated, so they asked whether leptin might have an effect on the immune cells. They found that in obese mice and humans, the increased leptin level contributed to the dysfunction of T cells, and in mice with melanoma, it reduced the T cells’ ability to control tumor growth.

One of the ways that the researchers could tell that the T cells were exhausted was by detecting a particular molecule known as PD-1 on their surface. Normally, PD-1 acts as a brake on T cells, keeping them from getting out of control; however, when T cells have too much PD-1, they become too exhausted to fight infection or cancer. The researchers found that PD-1 was more abundant on T cells in obese tumor-bearing mice and humans than in their non-obese counterparts, and this was partially due to increased leptin levels.

To see if they could use this finding to their advantage, the researchers treated tumor-bearing mice with an antibody that blocks PD-1. (Multiple antibodies against PD-1 have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of certain types of cancer.) What they found was that the treatment awakened the T cells and reduced the size of the tumors in obese mice to a much greater extent than in non-obese animals. This difference was likely due to the greater abundance of PD-1 available for the antibody to target in obese mice. Although it may appear that obesity paradoxically improved the response to immunotherapy, it is important to note that the anti-PD-1 antibody mainly leveled the playing field by reducing the detrimental effect of obesity on the immune response.

But people are not mice, so were these results relevant to patients? To find out, the team took a look at patients with melanoma and saw that the immune cells in patients with a body mass index over 30 had higher levels of PD-1 and other markers of exhaustion compared with non-obese patients. When patients with various types of cancer (including melanoma, lung, and ovarian tumors) were treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody, obese patients experienced greater improvement in outcomes than non-obese patients. With these observations, the researchers confirmed what they saw in the mouse studies — that obesity also affected T cell function and response to immunotherapy in people.

For a more in-depth analysis of this study, visit ACIR.org.

by Anna Scherer